Duke of Wooster-shire

Donald Morrison

To millions of readers in scores of languages around the world, the

name P.G. Wodehouse evokes a mirthful Edwardian realm of hapless

dukes, fearsome maiden aunts and one very tolerant, quietly competent

valet. Wodehouse, who died in 1975 at the age of 93, remains one of

the best-loved English writers. Nearly all of his 100-odd novels and

story collections are still in print. Wodehouse magazines and fan

clubs dot the globe. Hardly a decade passes without a new movie or

play inspired by his creations: the dim but affable Bertie Wooster,

his long-suffering gentleman's gentleman Jeeves and their screwball

cohorts at Blandings Castle and the Drones Club.

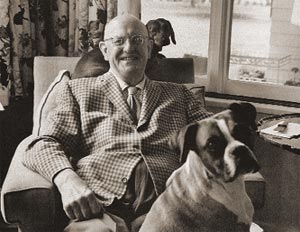

GENIUS IN EXILE Wodehouse, circa 1960, relaxes with friends in his Long Island home

GENIUS IN EXILE Wodehouse, circa 1960, relaxes with friends in his Long Island home

So rich is Wodehouse's legacy that it is difficult to understand why

he almost destroyed it. As Robert McCrum recounts in his exhaustive,

elegantly written Wodehouse: A Life (Viking; 530 pages), the author

was at the peak of his popularity when, in 1941, he made a series of

wartime broadcasts for the Nazis while interned in Germany. He was not

coerced, but he clearly misjudged the seriousness of his action. In

Britain, politicians denounced him in Parliament and columnists in

print. Libraries withdrew his books. The British government

investigated him for treason, and editors wouldn't touch his writings

with a cricket bat. The man whose vision of Britain is now engraved in

the popular mind could not go home again. Concludes McCrum, literary

editor of Britain's The Observer: "The Second World War finished

Wodehouse."

Not quite. He found a new home and, eventually, even greater fame

after the war. As McCrum also notes, Wodehouse was every inch the

Edwardian: calm in a crisis, aloof but generous (he supported an old

school chum for years), quietly productive (he could pound out a

novel's first draft in days), and fit as an oak (thanks to daily

calisthenics). Many of those qualities can be traced to Wodehouse's

Woosterish upbringing. A descendant of Norfolk nobility, including a

sister of Henry VIII's ill-fated wife Ann Boleyn, Pelham Grenville

Wodehouse rarely saw his parents ║ a colonial administrator and his

dour wife. The young "Plum," as Pelham was nicknamed, was raised by

nannies and schoolmasters to become an athletic but bookishly solitary

child, reading the Iliad at age 6 and penning his first story at 7.

When his parents refused to fund him at Oxford, he joined a London

bank, writing at night and resigning as soon as he could support

himself as a freelancer.

Wodehouse's heart was in musical comedy. He was writing lyrics for

London's West End in his 20s, and by 1917, five shows featuring his

lyrics were playing simultaneously on Broadway. Commuting to the U.S.,

Wodehouse collaborated with Jerome Kern, George and Ira Gershwin and

Cole Porter. "Musical comedy was my dish," Wodehouse wrote of those

happy days. "I would rather have written Oklahoma! than Hamlet.'"

But the real money was in Wooster-shire. After a stream of popular

stories about well-born wastrels, among them Bertie Wooster, Wodehouse

introduced a valet named Jeeves. He paired the two to solve plot

problems in The Man With Two Left Feet (1917), and the rest is

history. To the many theories about the characters' origins, McCrum

insightfully adds: "The cunning servant■foolish master has been a

staple of comedy since classical times, and Wodehouse certainly knew

his Plautus and his Terence." By the 1920s, magazines like Liberty and

The Saturday Evening Post would pay up to $35,000 to serialize a

Wodehouse novel. At the dawn of the Depression, he had a Mayfair

mansion and a Rolls Royce with his crest on the door.

Money led to his downfall. Tax authorities in the U.S. and Britain

began to pursue those royalties, so Wodehouse fled to the northern

French resort of Le Touquet. There in May 1940 he was seized by the

German army. For 13 months he was held in a succession of camps, where

fellow inmates report that he helped keep morale high and shared his

worldly goods with them. Shortly before being freed, he agreed to give

five radio talks for his fans in the U.S., which had not yet entered

the war (an event the Germans hoped his reassuring words could

forestall). Not realizing how desperate Britain's plight had become

since his capture, he produced a breezy account of camp life. "There

is a good deal to be said for internment," he observed in the first

broadcast. "It keeps you out of the saloons and gives you time to

catch up with your reading."

He spent the rest of his life regretting that lapse. Even before the

war ended, British officials dropped plans to prosecute Wodehouse, but

the decision was not made public until after his death. He exiled

himself to the U.S., where he was viewed with suspicion, and his

stories of dukes and butlers were deemed out of touch. "I sometimes

wish I wrote that powerful stuff the reviewers like so much, all about

incest and homosexualism," he half-joked. Wodehouse lived in

near-seclusion in Long Island, New York, with his wife Ethel (their

daughter Leonora died in 1944) as he ground out yet more tales of his

fantasy world. Increasingly, as modern life coarsened and Cold War

anxieties deepened, people decided they liked his world better than

theirs.

His countrymen eventually forgave his wartime indiscretions. He was

granted a knighthood six weeks before he died. Today the Oxford

English Dictionary contains 1,600 Wodehouse citations, and scholars

dissect his writings for a depth that isn't really there. What is

there, as fans can attest, is a timeless, effervescent cocktail of

comic juxtapositions, smoothly musical prose and exuberant generosity.

"Behind the Drones and the manor house weekends," writes McCrum, "is a

sweet, melancholy nostalgia for an England of innocent laughter and

song." An England that Wodehouse, after his thoughtless blunder, never

saw again.

|