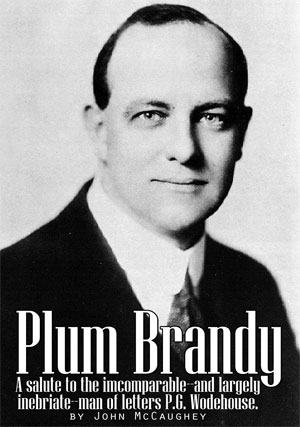

Plum Brandy

John McCaughey.

P.G. Wodehouse— ”Plum” to his friends—is arguably the 20th Century’s finest

writer of English prose.

P.G. Wodehouse— ”Plum” to his friends—is arguably the 20th Century’s finest

writer of English prose.

He was certainly the funniest. Most famous for his creation of Bertie

Wooster, the lovable if vapid rich young man of many cups, and his

Gentleman’s Personal Gentleman (or valet, if you prefer) Jeeves, whose main

job is, by sheer brain-power, to extricate the Young Master from

innumerable scrapes.

During his long life (he died, working until the end, in 1975 aged 93),

Wodehouse was prodigiously prolific: turning out more than 100 novels and

300 short stories, as well as innumerable plays, articles and song lyrics.

It would nearly take one longer to read the collected oeuvre than it took

Wodehouse to write them.

With regard to booze, Wodehouse lived and worked in a far more relaxed

world than today’s constipated politically-correct society and he exploited

that boozy atmosphere to marvelously-amusing effect.

In a sort of concordance called Wodehouse Nuggets (1983), chronicler

Richard Usborne makes great sport by identifying 30 of the Master’s

wonderful similes for being plastered or hungover. There are too many to

quote in full, but the highlights include:

"Insidious things (mint juleps). They creep up on you like a baby sister

and slide their little hands into yours and the next thing you know the

Judge is telling you to pay the clerk of the court $50.”

"If you want real oratory, the preliminary noggin is essential. Unless

pie-eyed, you cannot hope to grip.”

"The barman recommended a ‘lightning whizzer’, an invention of his own. He

said it was what rabbits trained on when they were matched against grizzly

bears and there was only one instance on record of the bear having lasted

three rounds.”

"He woke next morning on the floor of his bedroom and shot up to the

ceiling when a sparrow on the windowsill chirped unexpectedly.”

"He tottered blindly towards the bar like a camel making for an oasis after

a hard day at the office.”

Geoffrey Jaggard, another Wodehouse chronicler, in his Wooster’s World

(1967), details a vast and sparkling array of the Master’s synonyms for the

state of being deep in one’s cups. These include (sit back, pour yourself a

stiffish one, and savor this vast vocabulary):

Under the surface; Completely sozzled; Fried to the tonsils; A tissue

restorer; Full to the back teeth; Lathered; Suffering from magnums; Not to

mention:

Lit a bit; Shifting it a bit; Mopping the stuff up; Off-Colour; Oiled;

Ossified; Pie-eyed; Plastered; Polluted; Primed to the sticking point;

Scrooched; Squiffy; Stewed; Stinko; Tanked to the uvula; Tight as an owl;

and Under the sauce.

A few last quick ones?

Whiffled; Woozled; Awash; and, finally, the Green Swizzle. Inevitably, all

that lathering led to more than a few rough mornings and Wodehouse

identified six varieties of hangover, namely:

The Broken Compass, the Sewing Machine, the Comet, the Atomic, the Cement

Mixer and, of course, the Gremlin Boogie.

One of Wodehouse’s most sublime passages, ranked justifiably by Jaggard as

“unquestionably one of the finest pieces of sustained humor in the

language” is the episode in which Gussie Fink-Nottle is selected (faute de

mieux) by Bertie’s Aunt Dahlia to hand out the annual prizes to the

schoolboys at Market Snodsbury Grammar School.

Understandably nervous and unaccustomed to such a chore, Gussie gets

entirely plastered beforehand—affording Wodehouse the opportunity to put to

page one of his funniest-ever scenes in literary history.

His Olympian intellect aside, Jeeves is famous for two especial drinks. One

is a corpse reviver for young men inflicted with what Wodehouse delicately

calls “a morning head.” Wodehouse does not specify, but avers that this

concoction will cure anybody short of an Egyptian mummy. The epitome of

modesty, Jeeves confesses to Aunt Dahlia that he has never actually tried

it on a corpse.

From what one gathers, it is a species of Bloody Mary fortified with

unusually generous amounts of red pepper, Worcestershire Sauce and egg

yolks.

Its initial, but only momentary disadvantage is to cause the eyeballs to

pop from their parent sockets and to ricochet off the opposite wall. After

the first sips, as Bertie puts it, “It felt as if someone had touched off a

bomb inside the old bean and was strolling down my throat with a lighted

torch.”

But after that, full health is restored and young gentlemen are ready for a

luncheon of a dozen lamb chops and a battered pudding. “Young gentlemen,”

Jeeves informs Bertie, “have told me that they have found it extremely

invigorating after a late evening.”

Jeeves’ second select concoction is a cocktail which he terms the Special.

Bertie calls it “rare and refreshing” and notes that it will turn a lamb

into a lion and, indeed, vice versa. Maddeningly, Wodehouse offers no clue

whatsoever as to the contents of the Special. I think it the solemn duty of

each generation of Wodehouse scholars to attempt to solve this greatest of

literary and spirituous puzzles—in my mind, far more important than the

puzzle of who actually wrote Shakespeare’s plays.

Jeeves’ grave and sage philosophy towards booze is encapsulated perfectly

at the end of another Wodehouse story. To extricate the Young Master from a

fearful fracas at a country house visit, Jeeves finds it necessary to

explain that Bertie was in fact under the clandestine observation of Sir

Roderick Glossop, the eminent “nerve specialist” or loony doctor.

Bertie is appalled to learn of this and, minutes before the dinner gong,

demands of Jeeves how he can go down to dinner when the other ten or so

country house guests believe that he is off his rocker.

But you can’t rattle Jeeves.

“My advice, sir, would be to fortify yourself for the ordeal.”

“How...?”

“There are always cocktails, sir. Shall I pour you another?”

|